A friend was searching far and wide for a ï¬rst officer to fly an exquisite Falcon 2000EX EASy, but couldnâ€ t ï¬ll the position despite the six-ï¬gure starting salary accompanying it. The company had advertised, offered hefty referral fees, upped the salary and beneï¬ts package—and still came up empty-handed.

t ï¬ll the position despite the six-ï¬gure starting salary accompanying it. The company had advertised, offered hefty referral fees, upped the salary and beneï¬ts package—and still came up empty-handed.

Iâ€ d sent him pilots for other jobs in the past, but by this time my own cupboard was bare. Everyone I knew who was even remotely qualiï¬ed for this kind of gig was already fully employed.

d sent him pilots for other jobs in the past, but by this time my own cupboard was bare. Everyone I knew who was even remotely qualiï¬ed for this kind of gig was already fully employed.

How We Got Here

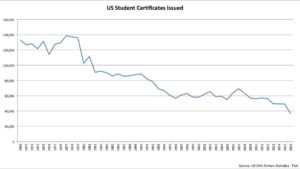

This conundrum started many years ago. Sometimes it feels like it was in a galaxy far, far away, too. It cost me $4,000 to earn a private pilot certificate in 1998. Can you imagine? That same certificate at the same FBO will set you back four times as much today. Higher fuel prices, insurance rates, maintenance and parts prices, and a shrinking industry ratchet up the costs for those who remain. Some are forced out of the game altogether, while others never get a chance to start.

Weâ€ re all familiar with the downsizing, mergers, furloughs, and bankruptcies that rippled throughout the aviation world after 2001. Flying careers had already lost much of their luster and accessibility even before the walls closed in post-September 11.

re all familiar with the downsizing, mergers, furloughs, and bankruptcies that rippled throughout the aviation world after 2001. Flying careers had already lost much of their luster and accessibility even before the walls closed in post-September 11.

Ironically, this mid-2009 timeframe was almost the exact moment the mandatory retirement age for airline pilots was raised to 65. This effectively masked the avalanche of Part 121 retirements for another half decade. And while the existing pilot workforce was growing older, there were precious few people training to replace them. The chasm was growing right before our eyes, but most were not sage enough to recognize what was happening—rumors of pilot shortages have been a part of almost every decade since the Wrights invented the airplane.

Business Aviation vs. The Airlines

While the major airlines seem to be holding their own when it comes to recruitment, theyâ€ re doing so largely at the expense of business aviation and regional airlines. Christopher Broyhill wrote in Decemberâ€

re doing so largely at the expense of business aviation and regional airlines. Christopher Broyhill wrote in Decemberâ€ s Business Aviation Advisor that the majors used to rely on the military for a steady supply of aviators, but now “target business aviation pilots, because they have time in sophisticated aircraft and are a known commodity when it comes to training and upgrade.â€

s Business Aviation Advisor that the majors used to rely on the military for a steady supply of aviators, but now “target business aviation pilots, because they have time in sophisticated aircraft and are a known commodity when it comes to training and upgrade.â€

This labor shortage may prove far more challenging to solve than even the industry itself has realized, because the skill set required of business aviation pilots extends far beyond that required of an airline pilot.

Airlines ply a limited route network, whereas business aviation can take you anywhere on the planet, and requires corporate and charter pilots to operate with greater autonomy and less support. My companyâ€ s director of operations once called to alert me about a trip to Pyongyang. (That flight was canceled, but during the planning stages I was surprised to ï¬nd that Jeppesen does include charts and data for North Korea. That wouldâ€

s director of operations once called to alert me about a trip to Pyongyang. (That flight was canceled, but during the planning stages I was surprised to ï¬nd that Jeppesen does include charts and data for North Korea. That wouldâ€ ve really given me a leg up when comparing destinations with other Gulfstream pilots.)

ve really given me a leg up when comparing destinations with other Gulfstream pilots.)

Business aviators must function at various times as flight attendants, managers, dispatchers,

instructors, mentors, recruiters, businessmen, accountants, and more. Some employers run steady and predictable schedules, but for most, the only constant is change. And letâ€ s face it, not everyone thrives in that environment. Many ï¬ne aviators lack the requisite skills, or simply have no interest in these sorts of challenges. Some of the talents are innate and cannot be taught—you either possess them or you donâ€

s face it, not everyone thrives in that environment. Many ï¬ne aviators lack the requisite skills, or simply have no interest in these sorts of challenges. Some of the talents are innate and cannot be taught—you either possess them or you donâ€ t.

t.

The charter industry has a unique challenge in the form of requirements from safety auditing ï¬rms such as ARG/US and Wyvern, which are ubiquitous components of the competitive Part 135 landscape. These auditors set standards that far exceed FAA minimums. This can have positive safety repercussions, but it may also reduce the pool of available candidates.

Solving The Problem

Will Rogers once said, “If you ï¬nd yourself in a hole, stop digging.†Doctors have the same philosophy: First, do no harm. In aviation terms, that means retaining existing pilots by providing compensation and quality of life that meet or exceed what others are offering. While that sounds pricey—and it is—itâ€ s almost certainly less expensive than replacing high-quality flight crew.

s almost certainly less expensive than replacing high-quality flight crew.

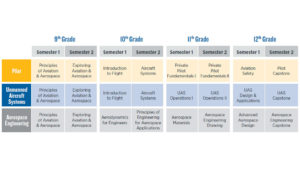

Second, since pilots require years of training and seasoning in order to qualify for corporate aviation or airline jobs, the critical role general aviation plays in the health of our industry has to be acknowledged. Light GA is the foundation of the proverbial food pyramid, providing the experience and opportunities necessary for building a well-rounded aviator, and it must be respected and nurtured if the rest of the aviation world is to thrive.

Achieving that goal will demand a reduction in the cost of light GA flying. This is one area where a modicum of progress can be seen: the Part 23 rewrite, a shift away from heavy-handed FAA enforcement policy, the availability of non-TSO avionics for the light GA fleet, and so on. But more must be done. Liability and tort reform would be an excellent place to start. Access to reasonable ï¬nancing options are another “must have†element of a healthy aviation ecosystem.

s You Can Fly program.

s You Can Fly program.

Weâ€ ve got to expose kids (and parents) to the wonder of general aviation at an early age, getting them out to the airport, bringing aviation-related STEM activity into their classrooms, and making airï¬elds a hospitable place for visitors again.

ve got to expose kids (and parents) to the wonder of general aviation at an early age, getting them out to the airport, bringing aviation-related STEM activity into their classrooms, and making airï¬elds a hospitable place for visitors again.

I know from ï¬rsthand experience what an outsized impact these accessibility efforts can have. In 1977, a kind TWA flight engineer spent a few minutes with me after a flight to St. Louis; Iâ€ m sure he forgot about the experience shortly thereafter. I didnâ€

m sure he forgot about the experience shortly thereafter. I didnâ€ t. Four decades later it remains an indelible and cherished memory. Itâ€

t. Four decades later it remains an indelible and cherished memory. Itâ€ s also part of why Iâ€

s also part of why Iâ€ m an international captain on a large-cabin Gulfstream today.

m an international captain on a large-cabin Gulfstream today.

Fixing the industryâ€ s employment shortfall is possible, but it wonâ€

s employment shortfall is possible, but it wonâ€ t be easy—or cheap. The market has turned, and the future belongs to those who embrace the change.

t be easy—or cheap. The market has turned, and the future belongs to those who embrace the change.

This article first appeared in the April, 2018 edition of AOPA Pilot Turbine Edition